When I first became a new ham, I was nervous to get onto a repeater and talk. So, I decided that I was going to find a simplex frequency that I could use with a friend to get some practice without much fear of a large audience. The frequency I had chosen was 146.465. Why I chose that frequency was because it was within the 2-meter band, as allocated by the FCC, it was displayed on the ARRL band chart for Technician licensees, and it was within the range of frequencies specified by the ARRL as use for simplex, and seemed far enough away from the 146.52 national calling frequency, so it seemed that it was going to work for me.

While I was correct in selecting a frequency within my Technician privileges, that frequency wasn’t the best one to choose, and I’ll tell you why in just a minute. At the time, I had heard of the Utah Band Plan, but I didn’t know what it was or where to find information about it. I eventually learned that the band plan further clarifies which frequencies were permitted by amateurs on each band, on top of what the ARRL specifies.

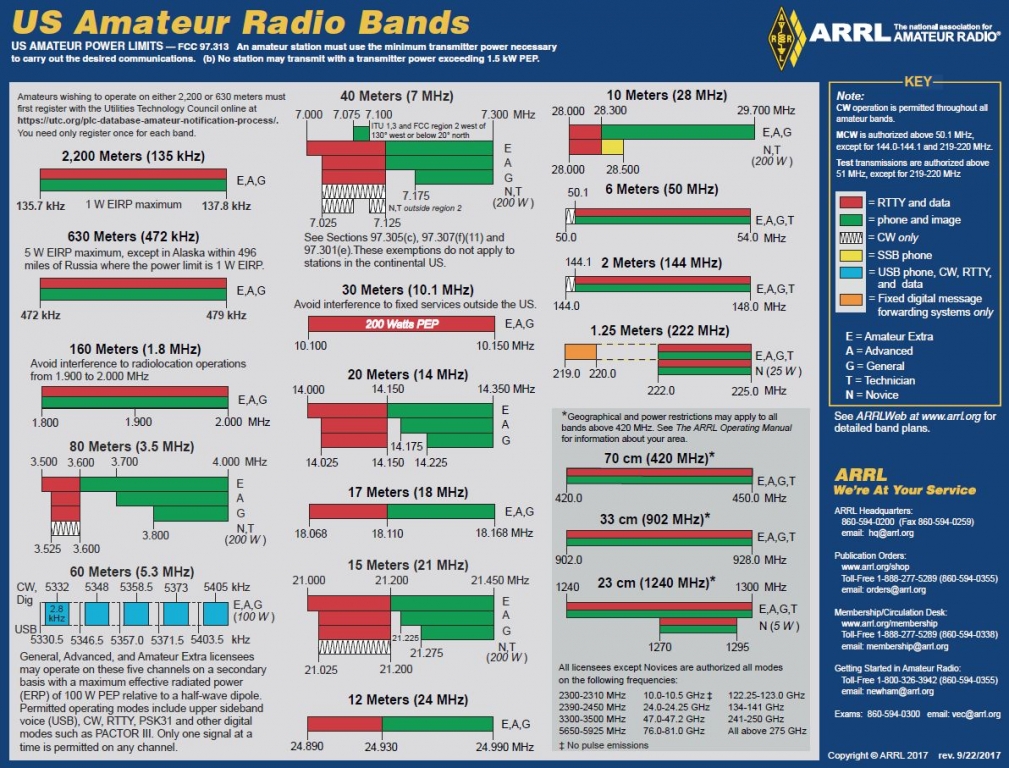

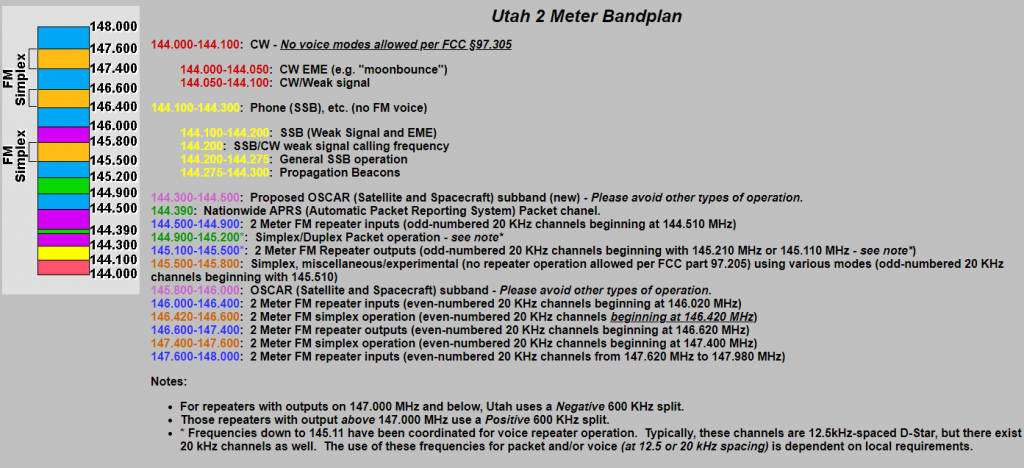

According to the ARRL band chart, anybody with a valid Technician license is indeed permitted to use any frequency in the 2-meter band, which spans 144.000 to 148.000 MHz. However, our local band plan states that certain sub-bands, or subsets of this span, are allocated for specific types of usage. The Utah Band Plan is laid out online at utahvhfs.org/bandplan1.html.

From the online list, you can see that the frequency I chose, 146.465, does fall within a sub-band set aside for simplex use. However, it doesn’t meet all of the requirements. What I didn’t take into account was how wide a signal can be. While you radio might be tuned to a specific frequency, that is just the center of the spectrum that can actually hear the transmission. When transmitting on wide-band, your 2-meter signal can be heard 12 to 15 khz, plus or minus 5 khz, to either side of the frequency displayed on your radio. That means that my transmissions could accidentally interfere with other transmissions, and our signals overlap. As a side note, this is one of the reasons why we are taught to not use the edge frequencies of the bands that we are transmitting on.

Another brief example to highlight another thing to keep in mind when selecting a simplex frequency. Say you chose the frequency 147.3325 MHz. According to the Utah Band Plan, that frequency falls within one of the sections allocated to repeater operation, and so does not meet the Utah Band Plan for simplex usage.

For simplex usage, you will need to choose a frequency from within one of the three sub-bands designated for simplex operation to be compliant.

Further examination of the Utah Band Plan shows that simplex frequencies must be selected by odd-numbered 20 kHz frequency separations in the 145.500 to 145.800 MHz list, and even-numbered 20 kHz frequency separations in the other two. This means, for example, you can use 145.510, 145.530, 145.550 MHz, etc., from the first list, and 146.480, 146.500, 146.520, etc., from the second list, and so forth. Therefore, a selection of 146.490 MHz, for example, for simplex operation goes contrary to the Band Plan.

Finally, a band plan is not the law, but it is a set of strongly suggested agreements that help us all play nicely with each other, in that they prevent chaos and minimize interference between stations. The band plan is set in place by the Frequency Coordinator, and in Utah is supported by the Utah VHF Society. Keep in mind that not all band plans between different states follow the same guidelines. So, if you travel to another state, don’t assume the band plan there is the same as what you’re used to; a little research can save you some heart ache